HISTORY LESSON FROM AN ECOLOGIST (Yes, this is outside my area of competency, but it's free! OK?)

In 1831-1838, the Government Land Office sent surveyors to mark the corners of the townships in Northwest Arkansas. As a reminder to those of you who are non-surveyor folks, a township is composed of 36, one-square mile sections. It is my understanding that the corners of the square mile sections were marked soon thereafter. The township of the Fayetteville area was named "Prairie Township". Go figure!

Please click on individual images to ENLARGE view.

Please click on individual images to ENLARGE view.

I cannot imagine what it must have been like to face the hardships of walking into the American wilds during that era to identify specific points on the planet that could be seen by others. The identifiers may have been a pile of rocks or a blaze on a tree, if one could be found nearby. It must have taken a hardy soul with a special wanderlust character to enter the world of surveying at that time, doing the work with not much more than a compass and two sticks with a chain in the middle.

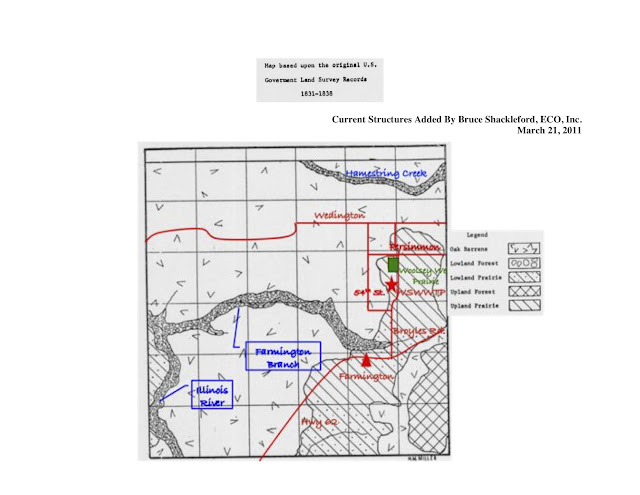

In the 1970's, a fellow named H.M. Miller did a Masters Thesis at the U of A that showed the plant communities from sketches, maps, and notes of the 1830's GLO surveyors. By looking at section lines and landmarks, I superimposed modern structures such as the Westside Wastewater Plant, various streets, and of course Woolsey Wet Prairie, onto Mr. Miller's drawing to get an idea of yesteryear's plant community of the area with regard to familiar landmarks (see attachment). Much of it was savanna, or "oak barrens" as they called it back then, and there were also areas of prairies and forests, both upland and lowland. The savannas had low density stands of large hardwoods, maybe 10 or 20 per acre. There was little brushy understory, and the ground cover was primarily herbaceous prairie plants, due to centuries of burning by Native Americans.

Some ten to twelve years before the surveyors adventures, in 1818-1819, the explorer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft described the praires of the region, sharing with us: "The prairies, which commence at the distance of a

mile west of this river, are the most extensive, rich, and beautiful, of any which I have ever seen west of the Mississippi river. They are covered by a coarse wild grass, which attains so great a height that it completely hides a man on horseback in riding through it. The deer and elk abound in this quarter, and the buffaloe is occasionally seen in droves upon the prairies, and in the open high-land woods."

Fast-forwarding to more modern times, I have tagged the two aerial photographs in the attached file to illustrate the vast changes that have occurred at the City-owned property on South Broyles Road, from the 1941 aerial photo to the 2010 aerial photo. Fruit orchards were at one time a common sight in Northwest Arkansas. In fact, the northern half of Woolsey Wet Prairie was once a fruit orchard, as was the dirt farm across the street on Broyles Road in 1941. Before the wetland cells were constructed and when the site was a hay field, you could see the remnants of where the rows of trees existed. Small earthen rows were present, and were interestingly built up and down over the prairie mounds and wetland depressions without plowing the mounds down. I wonder if the fruit trees did better on the mounds or the adjacent depressions? I suppose it was a function of whether it was a dry year or a wet year. Most of the prairie mounds of the area are in danger of extinction, and untold thousands have already departed, never to return.

Today, an apple tree and a pear tree near the north gate at Woolsey Wet Prairie appear to be the lone survivors of the pre-World War II orchards. Though severely damaged by age and elements, they still bear fruit. The pear tree in particular has especially sweet fruit, as I have heartedly raccoon-sampled them myself, picking up a spent limb from the ground under the old tree, to play piñata in seek of the succulent treasure. I believe they were there in the 1941 aerial photo, which means they are at least 70 years old. Hope I live that long, but then again maybe more, since that age is only 11 years away for me. Regardless, I do hope the fruit trees outlive me.

Likewise, the old barn standing today was there long ago, as shown in the 1941 aerial, along with several homes. A fellow named John Brumley once lived in the rock house that is now a mass of overgrown rock ruins, near the only remaining barn on the property. Brumley probably never realized, or even cared, that the catalpa tree in his front yard would become famous as the place where the second known siting of the Northern Shrike in the whole State of Arkansas would take place, earlier this month.... and he would certainly be aghast to look out his window to see a huge state-of-the-art wastewater facility that puts his outhouse to shame, and be told he would be required by law to tie into the sewer line that goes to it. That would have been so unimaginable to him that he would have probably thought that the Martians had landed in the South Forty when he saw the top of the big equalization basin!

Though I figured most, or all, of the Woolsey proximity was all a working farm back in the day, I spoke with Mrs. Jordan several years ago before the history she holds perishes forever, to find otherwise. As I recall, she said she had lived on Broyles Road since 1957. When asked about the historical land uses at our beloved mitigation site, she said that all of the Woolsey Wet Prairie area was once part of a Soil Bank and laid fallow for 10 to 15 years. The Federal Soil Bank Program of the late 1950s and early 1960s paid farmers to retire land from production for 10 years, and was basically the predecessor to today’s Conservation Reserve Program. Maybe that is why Woolsey's ancient seed bed of native plants was there to gladly reawaken when called upon, saving the City lots of money many years later. I wonder if they had to pull up all the fruit trees to be eligible to enter the Soil Bank program?

Another local elder, Richard Swafford, told me that corn, wheat, and beans had once been propagated on the City property in the 1930's, where the wastewater plant now churns, washing the water from dirty to clean, as told to him by previous generations. He still cuts hay from portions of the city property today, and has encountered a few drainage tiles with his tractor over the years, that were apparently installed to keep the wet prairie from being too wet for crops.

Though the mention of Woolsey Wet Prairie evokes few to think, or even know, about the tired and retired fruit trees; the rock house ruins where a family once slept, ate their meals, and raised there children; or the old barn where a calf or two had been born, they are very much elements of Fayetteville's heritage. The area has taken on a new persona from the 1830's to 1941 to 2010, yet still holds on to a very small morsel of what was commonplace in the past.

Perhaps the most important history and ecology lesson to be learned from seeing how our Woolsey Wet Prairie site has responded to a little nudging, is that much has been destroyed, but it's ALL restorable. Whether or not that is a fact or a myth may be a matter of perspective, but should, nonetheless, become a mindset before we run out of the ground and the other life that depends upon it who have lived here long before we did.

Nature has a unique way of repairing itself with a little help!

Hope you enjoy the history!

Bruce Shackleford

Bruce Shackleford, M.S., REM, REPA, CPESC

President, Environmental Consulting Operations, Inc.

17724 I-30, Suite 5A

Benton, Arkansas 72019

"Integrating ECOnomy and ECOlogy, since 1990"

office: 501-315-9009

mobile: 501-765-9009

No comments:

Post a Comment